Can You Develop Emotional Intelligence?

Emotional intelligence (EI) is one of those “sciences” that might be the key to success., or it might be a bunch of hooey. Who’s to know? While it might be hard to define emotional intelligence (although I have below, keep reading) we definitely know when it isn’t being exhibited. A three year old lying on the floor screaming “Nooo” lacks emotional intelligence. So does the forty year old who says “You can’t fire me because I quit!”

In today’s fast paced and tumultuous business climate, emotional intelligence is an important skill to have. We need to be able to accept challenges and frustrations, work with others cooperatively, accomplish assignments independently, participate in activities we might rather not, and so much more.

Talent Smart has been able to equate high performance in the workplace with high EI (and likewise poor performance with low EI [also known as EQ]). John Mayer, professor of psychology at the University of New Hampshire, is one of those who thinks that claim is hooey. But let’s assume that emotional intelligence IS a definable and measurable skill and that we’d like to develop it in our workforce.

Emotional Intelligence Defined

There are five “domains” or competencies of emotional intelligence:

Self-awareness (recognizing emotion and its effect, knowing one’s strengths and limitations)

Self-regulation (conscientiousness, adaptability, comfort with ambiguity)

Self-motivation (goal setting, commitment, optimism)

Social awareness (interest in others, empathy, understanding power relationships)

Social skill (communication, conflict management, leadership, etc.)

Each of these can be further broken down. For instance, conscientiousness can be further defined as keeping promises, fulfilling commitments, and holding oneself accountable.If we believe Talent Smart’s claims, these would be nifty markers on a performance evaluation, don’t you think? Do we assess people on their ability to complete their work correctly and in a timely fashion or are they really being assessed on their conscientiousness? Correcting poor performance would be quite different depending on whether you were assessing the visible output or the EI that underlies it.

Developing Emotional Intelligence

If we want to develop better performers in the workplace, it behooves us to examine whether we can develop emotional intelligence. Many of the things that we do when Teaching Thinking naturally align with increasing emotional intelligence. For instance. being open to and examining different perspectives. Let’s assume your company announced that there will be no bonuses this year. People with poor EI will think “that’s not fair!” while people with higher EI will realize the business climate has changed and the company acted accordingly.

To “teach” this skill we can include higher-order, open-ended questions in our training. Coaching and mentoring also help to develop emotional intelligence because coaches and mentors ask open-ended questions aimed at getting people to self-examine. Questions such as, What would you do differently next time? Who could be an ally? and What did you learn from this? get at examining and developing self-awareness – an important EI skill.

Another way to develop EI is to turn the coaching / mentoring idea around and have your trainees act as a coach / mentor. This assignment requires social awareness and the ability to empathize with others. The coach / mentor doesn’t have to be an expert. For example, providing feedback about an upcoming presentation requires the coach / mentor to consider the developmental needs of the presenter, frame feedback in a constructive way – taking in to consideration the emotions of the other person, and provide emotional support (you can do this!) – all EI skills. These are all great leadership skills too… but I digress.

So whether EI can be developed in others or not may be nebulous, the skills that lead to EI can and should be incorporated in to many aspects of the workplace (training, managing, performance reviews, and more).If you’d like to assess your own Emotional Intelligence, check out this short, on-line assessment.

How Case Studies Aid in Teaching Thinking

What is a Case Study?

Before we jump in to the value of using case studies to teach thinking, it’s prudent to define exactly what it is we are talking about. Case studies are a way to present content in a narrative format, followed by discussion questions, problems or activities. They present readers with an overview of the main issue, background on the organization or industry, and events or individuals involved that lead to the problem or decision presented in the case.

As in real life, there is rarely a specific answer or outcome. Case studies are typically tackled in groups, although they can be an individual assignment. Learners apply course concepts in real-world scenarios, forcing them to utilize higher-order thinking skills such as analysis, synthesis and evaluation.

Case studies are very beneficial in helping learners to bridge the gap between theory and practice. Using case studies puts the responsibility for learning on the learner himself, rather than relying on an instructor or facilitator to guide the learning process. Case studies model more real-world tactics despite the fact that the content is prescribed.

Case studies in a business environment are typically used as an activity to transmit the course content; requiring an hour to a few hours of work as part of the larger course requirements. While business-based case studies are generally focused on teaching business principles, The Training Doctor uses business-based case studies to teach thinking processes.

Case studies pack more experience into each hour of learning than any other instructional approach.

Skills Taught Through Case Study Usage

While numerous studies have concluded that case studies are beneficial to learning simply because they are engaging and participative, there are many social and business skills which are taught through the case study process, as well.

If you are familiar with Bloom’s Taxonomy, you know that the “higher” levels of learning outcomes are analysis and synthesis – which case studies are able to achieve by presenting lots of information pertinent to various aspects of the case, and asking the learner to dissect and/or combine that information to arrive at a well-reasoned opinion or solution.

Additionally, as much work in the 21st century is accomplished via teams, case studies provide an opportunity to learn critical business skills such as communicating, problem-solving, and group work dynamics in general. NOTE: It is wise to ensure learners understand group dynamics, meeting management, group process (such as decision making and conflict resolution) and the like, before sending them off to work as a team.

Often the benefits of the case study approach are lost due to the learner’s inability to manage themselves as a group (which is also an important learning outcome!).

Outcomes of Case Study Learning

In addition to skills learned via case studies, there are business outcomes which are achieved, as well. Real-world business activities are rarely cut and dry. They are dynamic and fluid which can be reflected in a case study much more easily than in the linear presentation of content which typically occurs via lecture.

Case studies prime the learner to look at an issue from multiple perspectives and – when used correctly – from multiple disciplines as well. By extrapolating a business case study to their own work environment, learners are able to grasp connections between topics and real-world application which is often difficult to do in a traditional instructor-led course.

While arriving at an answer or solution may be the stated objective of a case study (what should Fred do next?), a greater outcome is developing the learner’s ability to apply problem-solving (or opportunity revealing) management to disparate information. In organizations with workers who are more tenured, the ability to insert their own experience and knowledge is not only helpful in keeping them engaged but beneficial for younger members of the group to hear.

It is a best-practice, when using case studies in business, to utilize groups from various disciplines within the organization. Different disciplines will bring different insights to the case, allowing for a more thorough discussion. Hearing various perspectives also teaches an appreciation for the “big picture” and demonstrates the importance of gathering all relevant data. For instance, in many of our case studies we ask “Who are the stakeholders and what are their interests?” It is difficult to answer this question if the group is all from the same department or discipline, they simply don’t see the other possibilities.

Additionally, case studies model the reality of business – there will always be incomplete information, time constraints, competing interests and conflicting goals, and one must still make the best decision one can – recognizing that in business no decision is ever “the right one.”

Where Do I Find Case Studies?

You can order case studies from Harvard Business Review or subscribe to The Training Doctor newsletter (right here, at the top of the page) where we release three new case studies each quarter. Additionally, you can always click on the "case studies" category of blog topics, on this page, to view previously published case studies.

Twelve Weeks to Becoming the Manager of the Most Kick-ass Department in Your Company

As organizational development consultants, we are often tasked with creating activities or events that "move an organization forward." Clients ask us to solve problems related to communication, teamwork, poor workmanship, lack of commitment or accountability, and many other issues which stymie output and frustrate individuals.

Every organization is different, of course, but if you are a manager who would like to elevate your profile and your department's reputation, here is an activity that anyone can use to achieve both. All you need to do is commit to one hour per week for three months and follow the process below.

Week 1

This works better if your team is co-located. There is something to be said for looking your colleagues in the eye.) Bring together your team and have each person stand, state their name, their role, and declare how their role interacts with or is enmeshed with another person in attendance and their role. Repeat until everyone has spoken.Be aware: This will be an uncomfortable struggle at first, but by week 6 people will easily rattle off their inter-dependencies and accountabilities.

Weeks 2 - 6

At subsequent weekly 1-hour meetings add one-more-individual to the interdependency declaration. In other words, in week 1 each speaker must choose one other individual and declare how their role interacts with or is enmeshed with that person’s role. In week 2 they'll need to choose two other individuals. In week 3, they'll choose three other individuals, and so on. Slowly your department will begin to recognize how they are dependent on one another. This process works because it is visual, verbal, requires people to think to make the association, and is repeated week after week.

Weeks 4 - 6

Once people have the routine of choosing co-workers and declaring how they work together, "step it up" by having them add something about the other role that is frustrating, confusing or that they always wondered about. This might sound like, "I'm Susan Jones. I schedule the demo-rooms for the sales group. Sean Rhodes is one of my internal customers; he frequently meets with prospective clients in the demo rooms. Sean, I've wondered how far in advance you schedule meetings with prospects that need a demo. Is it usually the same-week or do you have more notice?"

What Susan is really getting at is, "I am tired of Sean always yelling at me that he has a client arriving within the hour and no where to put them." But perhaps Susan doesn't realize that Sean gets little advance notice himself. Or perhaps she just made Sean aware that he needs to schedule the demo rooms with more notice than he has been giving.

Further conversation can happen after your 1-hour meeting, allowing Susan and Sean to come to a solution so that neither of them regularly feels frustrated by the other (without your meeting, and this process, the chance of this conversation happening at all is slim and perhaps the whole "issue" would lead to a major blow-up down the road).

Weeks 7 - 12

Time to step it up again. Now that you've got your team regularly focusing on the way they work with and are dependent upon one another, start bringing in "guests" from other departments (directly upstream and downstream are easiest at the start). Stretch their knowledge of and accountability for other roles and departments. The same process is used, but now each speaker must include someone (the guest) outside your immediate group.

Let's assume you invited a mechanic from the maintenance group. This might sound like, "I'm Susan Jones. I schedule the demo-rooms for the sales group. I also issue a monthly report to maintenance for each machine, which logs how many hours each machine was used during the month."

Susan may or may not know that the hours-used report allows maintenance to conduct preventative maintenance on the demo-machines which are otherwise out-of-sight, out-of-mind for them. Preventative maintenance ensures that a salesperson isn't embarrassed by a demo-machine that fails during a client presentation. If Susan doesn't know that's what her report is used for, she'll learn it during your monthly meeting (by asking "I've often wondered what that report is used for,") and will understand the value and utility of it.

If Susan does know and declares the purpose of her report, the rest of the group will come to learn that this maintenance occurs unbeknownst to them in order to ensure the sales group has the equipment they need to be successful.

In addition to your current group of workers becoming more knowledgeable about, and accountable to, their co-workers and the larger organization, this is a great process for bringing new hires into the fold. They will quickly understand the work processes and outputs of your department and how they are interrelated, which is crucial to doing their own job well and knowing who to ask for help.

In just 12 short weeks you'll have the most highly functioning department in your organization, guaranteed.

Drop us a line and tell us how it went. And don't be stingy! When other managers ask how you created such a high-functioning team - share the process, like we just did for you.

Are You A Slow Thinker? Good for you!

First, a quick tutorial on Fast and Slow thinking – or System 1 and System 2 Thinking as popularized by Nobel Prize winner Danny Kahneman - in case you are not familiar.

Fast / System 1 Thinking

System 1 thinking can be thought of as our “immediate response” to something. When the alarm goes off in the morning – we get up. We don’t stop and ponder – what is that noise? what does it mean? should I get up right now? There is an immediate understanding of the information coming in and an immediate and knowledgeable response to that information. (Caution! This sometimes leads us to applying bias to situations that do in fact require more thought, and System 1 can be manipulated through the use of priming and anchoring.)

System 1 also enables us to do several things at once so long as they are easy and undemanding. System 1 thinking is in charge of what we do most of the time.

However, you want system 2 to be in control.

Slow / System 2 Thinking

System 2 thinking is the kind of thinking that requires you to struggle a bit. In this short (4:22) video featuring Kahneman, he gives the example of being able to answer 2x2 vs. 17x24.

The latter causes you to pause and put more mental energy in to arriving at the answer. If you’d like to try a fun activity to test your slow thinking ability, click here. Or watch the famous Invisible Gorilla video which illustrates that when System 2 is concentrating on one thing (counting the number of passes) it cannot concentrate on another (seeing a gorilla walk through the frame).

With practice System 2 can turn in to System 1 thinking, as in the case of a firefighter or airline pilot. Once sufficient application of System 2 thinking has occurred over an extended period of time and in varying circumstances, it becomes “easy.”

System 1 is all about “knowing” with little effort – as an expert is able to.

System 2 Thinking in Learning

What does System 2 Thinking mean for learning in organizations? Quite a lot, actually.

In a recent blog post by Karl Kapp, in which he describes purposefully causing his students to struggle, he states, “Unfortunately most learning is designed to avoid struggle, to spoon feed learners. This is not good… The act of struggling and manipulating and engaging with content makes it more meaningful and more memorable.”

Another important job of System 2 thinking is that it is in charge of self-control. This is an important skill / quality in the workplace. It allows us to measure the information coming at us and respond appropriately (which means, sometimes, not responding at all). Controlling thoughts and behaviors is difficult and tiring. Unfortunately many people find cognitive effort unpleasant and avoid it as much as possible (so says Kahneman in Thinking Fast and Slow).

Because of this tendency, we need to make teaching thinking skills a priority in workplace learning and development. This could be a challenge. Tim Wu, a professor at Columbia Law School, says that older Americans may be better equipped for serious thinking because they didn’t grow up with smartphones and can “stand to be bored or more than a second.”

And a study conducted at Florida State University determined that a single notification on your phone weakens one’s ability to focus on a task. The ability to focus is crucial not only in completing tasks but in learning new things as well. The ability to focus without distraction and to perform cognitively demanding tasks is THE job skill of the future.

Accelerate Learning through On-the-Job Assignments

Giving individuals assignments that complement their work, or allow them to experience new opportunities, abound inside companies, but we rarely ask workers to do anything outside their normal responsibilities. Here are some ideas to provide individuals with more business insight and experience without a formal learning process:

Giving individuals assignments that complement their work, or allow them to experience new opportunities, abound inside companies, but we rarely ask workers to do anything outside their normal responsibilities. Here are some ideas to provide individuals with more business insight and experience without a formal learning process:

- Train a new hire or develop an orientation process for new hires to help them to be productive as soon as possible

- Develop a ‘calendar of events’ for your role which would enable someone else to take over in an emergency – what are the things that are required daily, weekly and monthly

- Conduct competitive intelligence

- Organize a lunch and learn with a guest speaker in your industry

- Create a master-mind group for your role / function

- Write a blog article “10 things XXX should know about XXX” (such as 10 things patients should know about the in-hospital pharmacy or 10 things patients should know about dietary restrictions)

- Develop a presentation for other departments within the company that explains your department’s priorities and working processes

- Create a workflow chart for your department and look for opportunities

What are the skills that are developed from these very generic on-the-job assignments? Decision making, interviewing, coaching, writing, facilitating, analyzing, planning, speaking and more. With just a little thought you’ll be able to come up with more personalized learning experiences that will benefit both the individual and the company as a whole.

It Ain't Learning if it's Microlearning

Microlearning is the short-term, focused delivery of content or involvement in an activity. Lately I’ve seen a lot of chatter about best practices for “microlearning.” By most standards microlearning should be less than six minutes and often the suggestion is that it is no more than two minutes.

The thinking is that learners have the “capacity” to sit still and watch an informational tutorial for only so long before they’ll zone out, hit pause, or be interrupted by their work. Companies that create micro learning promote it by touting its ability to quickly close a “skills gap” – a learner can learn a new topic or take advantage of a refresher, in a short snippet that they can apply immediately. About to close a sale? Watch this microlearning video on 5 steps to closing a sale. Need to perform cardiac surgery? Look at this flowchart which will lead you through the process (I’m kidding. I hope.).

Another advantage – per proponents of microlearning – is that the learner himself can control what and when to learn.

Pardon my upcoming capitalization: THIS IS NOT LEARNING. This is performance support. How and when did we get these two terms confused?

Silo’d Learning is Limiting Workplace Learning Potential

For years, possibly decades, we have helped people develop expertise around specific jobs, or how to do their current job better. We've kept them learning "up" a topical trajectory, much like a silo.

What was often neglected was the need to expand knowledge, skills, and abilities overall. What we’ve got now are millions of Americans who are very skilled in a narrow area of expertise, but not well prepared for upper management or executive positions because they lack general business intelligence.

While it might seem obvious to only include salespeople in sales-training, what would be the detriment of including the administrative group that supports the salespeople, or the customer service representatives who support the customer after the sale, or the field service representatives who actually see the customer more frequently than anyone else, or manufacturing who will learn how their product works in the “real world?” Wouldn’t each of them learn more about how to do their job well, and learn more about the business as a whole by participating in a developmental topic that is ancillary to their current work?

Estimates are that by 2030, Baby Boomers will be completely out of the workforce. This presents a call to action and an opportunity, because the generation with the most breadth and depth of work experience will be leaving the workforce. We – as L+D departments and professionals – need to quickly rectify the silos of specialists we’ve created by broadening the role-specific training of the past in order to address the workforce needs of the future.

Our challenge is to develop a new generation of company leaders capable of making well-rounded and well-informed decisions based on their experiences in a multitude of business areas. The focus on job-specific training is a thing of the past. Organizations must focus on developing well-rounded individuals who can take the organization into the future. The future success of our companies depends on the actions we take today to develop our future workforce.

Better Learning Through Interleaving

Interleaving is a largely unheard of technique – outside of neuroscience - which will catapult your learning and training outcomes. The technique has been studied since the late 1990’s but not outside of academia. Still, learning and incorporating the technique will make your training offerings more effective and your learners more productive.

What is it?

Interleaving is a way of learning and studying. Most learning is done in “blocks” – a period of time in which one subject is learned or practiced. Think of high school where each class is roughly an hour and focuses on only one topic (math, history, english, etc.). The typical training catalog is arranged this way, as well. Your organization might offer Negotiation Skills for 4 hours or Beginner Excel for two days. The offering is focused on one specific skill for an intense period of time.

Interleaving, on the other hand, mixes several inter-related skills or topics together. So, rather than learning negotiation skills as a stand-alone topic, those skills would be interleaved with other related topics such as competitive intelligence, writing proposals or understanding profit-margins. One of the keys of interleaving is that the learner is able to see how concepts are related as well as how they differ. This adds to the learner’s ability to conceptualize and think critically, rather than simply relying on rote or working memory.

How Does it Benefit?

Interleaving is hard work. When utilizing interleaving, the brain must constantly assess new information and form a “strategy” for dealing with it. For example, what do I know about my competitor’s offering (competitive intelligence), and how am I able to match or overcome that (negotiation skills)? While the technique is still being studied, it is suspected that it works well in preparing adult learners in the workplace because “work” never comes in a linear, logical or block form. You might change tasks and topics three times in an hour; those tasks may be related or not –the worker needs to be able to discriminate and make correct choices based on how the situation is presented.

Interleaving helps to train the brain to continually focus on searching for different responses, decisions, or actions. While the learning process is more gradual and difficult at first (because there are many different and varied exposures to the content), the increased effort results in longer lasting outcomes.

What’s interesting is that in the short term, it appears that blocking works better. If people study one topic consistently (as one might study for a final exam), they generally do better – in the short term - on a test than those who learned through interleaving.

Again, the only studies that have been done have taken place in academia, but here is an example of the long-term beneficial outcomes of interleaving. In a three-month study (2014) 7th-grade mathematics students learned slope and graph problems were either taught via a blocking strategy or an interleaving strategy. When a test on the topic was conducted immediately following the training, the blocking learners had higher scores. However, one day later, the interleaving students had 25% better scores than the blocking learners and one month later the interleaving students had 76% better scores! Because interleaving doesn’t allow the learner to hold anything in working memory, but instead requires him to constantly retrieve the appropriate approach or response, there is more ability to arrive at a well-reasoned answer and a better test of truly having learned.

How Can You Use Interleaving?

As mentioned earlier, although concentrating on one topic at a time to learn it (blocking) seems effective, it really isn’t because long term understanding and retention suffers. Therefore one must question whether there was actual learning or simply memorization. If your goal is to help your trainees learn, you’ll want to use an interleaving process. Warning: Most companies won’t want to do this because it is a longer and more difficult learning process and the rewards are seen later, as well.

Make Links

The design and development of your curriculum(s) doesn’t need to change at all – simply the process. First, look for links between topics and ideas and then have your learners switch between the topics and ideas during the learning process. For instance, our Teaching Thinking Curriculum does this by linking topics such as Risk, Finance, and Decision Making. While each of those is a distinct topic, there are many areas of overlap. In fact, one doesn’t really make a business decision without considering the risk and the cost or cost/benefit, correct? So why would you teach those topics independent of one another?

Use with Other Learning Strategies

Interleaving isn’t the “miracle” approach to enhanced learning. Terrific outcomes are also achieved through spaced learning, repeated retrieval, practice testing and more. Especially when it comes to critical thinking tasks, judgement requires multiple exposures to problems and situations. Be sure to integrate different types of learning processes in order to maximize the benefit of interleaving.

Integrate Concepts with Real Work

Today’s jobs require people to work on complex tasks with often esoteric outcomes. It’s hard to apply new learning to one’s work when the two occur in separate spheres and the real-world application isn’t immediate. Try to integrate topics to be learned with the work the learner is doing right now. For example, for a course in reading financial reports (cash flow, profit/loss, etc.), rather than simply teaching the concepts with generic examples of the formats, the learners were tasked with bringing the annual report from two of their clients (learners were salespeople). As each type of financial report was taught, the learners looked to real-world examples (that meant something to them) of how to read and interpret those reports.

Ask the Learners to Process

Too often we conclude a training class by reviewing what was covered in the class. Rather than telling the learners what just happened, have them process the concepts themselves. This is easiest to do through a writing activity. You might ask the learners to pause periodically, note what they have learned, link it to something they learned earlier, and align it with their work responsibilities. For instance: I will use my understanding of profit margins and financial risk to thoughtfully reply to a customer’s request for a discount or to confidently walk away from the deal. It’s not about the sale, it’s about the bottom line. The process of writing helps the learner to really think through the concepts just taught and it allows them to go back over their learning in the future to remind themselves of the links they made within the curriculum and between the curriculum and work responsibilities. Interleaving enables your training to be more effective and your learners to be more accomplished and productive.

Why do so Many Companies Get Training Wrong?

Earlier in 2017 I was interviewed by the BBC for an article on workplace training and specifically, why companies get it wrong so often. As one of a few expert sources for the article, my entire response was not included, but I wanted to share it with you here.

WRONG: Cram all the learning in to the shortest amount of time possible

Solution: Mete it Out Over Time

One of the biggest contributors to the lack of training effectiveness is that we simply don’t allow enough time for training. First, companies have cut what used to be an 8-hour training day back to 4 hours, or two hours, in many cases. Sometimes it’s even been turned into a boring PowerPoint self-study (this violates a lot of adult learning principles, but we won’t go there today).

Secondly, in combination with the shorter time allotted for training, we deliver all the content in one “sitting.” While this is a great approach for an overview or introduction to a topic, it never develops into learning and skill. So the first thing we must do to make workplace training better is to mete the content out, over time. Learners need an introductory period, a practice period, a period for reflection and a period for perfection. This process cannot be compressed into 4 hours. The brain doesn’t process new information that way and the body doesn’t develop the muscle memory or finesse it needs to perform a skill this way either. (Here is an interesting article on the benefits of spaced learning in training medical professionals.)

WRONG: Teaching things in "theory"

Solution: Real World Application

This best practice has two angles. The first goes hand-in-hand with the meted content suggested above. If you are going to space the learning out over a period of time, you have the ability to assign real-world activities to the learners. This allows them to put what they’ve learned into practice and develop a better understanding of the concept as well as the muscle memory required to perform it. For example, in a sales training course, if step one is to identify prospects – the assignment should be to return to the next lesson having identified and vetted at least three prospects using the skills taught in lesson one. The assignment after lesson two should be to again start at prospecting and then add step two. This allows the leaners to learn-do-reflect-perfect.

The other angle is to have learners work with real-world concepts during the learning time itself. You could have a training class that teaches learners to read financial statements such as profit and loss, cash flow, etc. in a “vacuum,” or you could have them learn to read these same reports while looking at the annual report for their own company, or their competitor. Rather than learning things in “theory,” have your workers learn the same concepts with real-world benefits.

WRONG: Not including management in the training process

Solution: Management Involvement

Management involvement is crucial for real learning in so many ways. First, it is important that managers understand what their workers are learning so that they can reinforce it (how many of us conduct a manager’s overview or ask for their participation before their workers come to us?). Second managers can assist in the practice/perfection phase of training by allowing their workers extra time to complete their newly learned processes (in other words suspending metrics during the practice phase) and by answering questions or providing coaching. Finally, managers are the best choice for evaluating the true outcomes of training. They are the ones who see if the workers are able to truly implement what they learned on-the-job.

WRONG: Having no real plan for training: who gets trained, in what, and why?

Solution: Make it a Strategy

I can’t decide if this failure is the most damning, or if the way we slice and dice content to cut it back to the most minimal amount of time it will take to transmit it is; so this is either #1 or #2 in terms of what companies do wrong when training their workers. For years now – decades- we have trained people in silos (if you are a salesperson all of your learning will be related to sales, somehow) and we administer training on an as-needed basis. If you are good at what you do, are performing well and aren’t in-line for a promotion – you could go years with no training at all. But in order to develop our workers, and our organizations, training needs to be a strategy. What could we teach someone that would make them that much better of a performer? Some “generic” topics that come to mind are finance, continuous improvement, and project management. There is no person in the workplace that couldn’t benefit from having these three skills; yet, if you aren’t a project manager, you’ll probably never get project management training. Companies are short sighted and tend to compartmentalize training as a “department” rather than utilizing training as a strategy that can make their organization better. If companies developed a strategic plan for employee development – like they do for company initiatives such as product launches or facilities expansion – in no time at all they would reap the rewards of a more capable, productive workforce. What are your thoughts? Why do so many companies get training wrong? You can see the original BBC article here.

Teaching Thinking through Adapted Appreciative Inquiry

If you've been a reader of this blog for any period of time, you know that using questions is something we regularly advocate for in order to change people's thinking and thereby change their behavior on the job.

But what if your learners have no preconceived notions on a topic to begin with? What if we don't want to change their thinking, we simply want to e x p a n d their thinking? That's when Appreciative Inquiry can be an excellent tool for teaching thinking skills.

Appreciative Inquiry, in its purest sense, is used as a change management /problem solving tool. Rather than gathering people (managers, workers, etc.) together and asking "What's going wrong, and how do we fix it?" Appreciative Inquiry instead asks, "What are our strengths? What are we great at? How can we maximize that and build on it to achieve excellence?"

Appreciative inquiry has been around since the late 1980's but hasn't been "in the news" much in the last decade or so. Perhaps it's time to revitalize the approach, with a different spin - let's use it to teach thinking. The way we envision using the technique is through possibility summits which help newer or younger associates within a company to help set the course for the future. Too often, when individuals have been with a company 20, 30 or 40 years, they are set in their ways. Why change? Things are working great.

But organizations that rest on their laurels are organizations that will ultimately fail. Younger associates may have great ideas but no knowledge of how to advocate for them or execute them. Appreciative Inquiry can help individuals and organizations to thrive. Here's how....

Adapted Appreciative Inquiry Process

Allow the "younger generation," if you will, to help envision the future and empower them to create it by utilizing an adapted Appreciative Inquiry Process:

First, craft questions that help to open up future lines of inquiry, such as "What is your vision (not expectation) for our company in five years?" "What do customers love about us?" "What are our strengths in __________ area or department?" Questions should be crafted to get at opportunities, competencies, and business ecosystems (such as working in conjunction with suppliers, competitors or customers). A more inspirational or free-flowing question might be: "It's 2025 and Fortune Magazine has just named us the most _______ company in America. How did we get there?"

Next, assign people who are newer in the organization to interview those with more tenure - using the questions created in the first step. This accomplishes two things: It devoids the idea that those at the top of the organization know best and opens up channels of conversation - It helps to develop relationships between people who might not normally interact in their day-to-day roles (for example, the CEO of the company being interviewed by someone in the shipping department), and the results of that can be amazing, not only for inspiration but for goodwill and long-term relationships.

Third, those who have conducted the interviews report back on what they've learned, and themes (strengths) and actions items are culled from the results.

Finally, the action items are prioritized (what can be done most quickly, what can be done most affordably, what will get us to our ultimate vision for the future, etc.) and assigned. Ideally, multi-tenure teams will be assigned to work on the action items, which helps to establish mentorship even if the company doesn't have a formal mentoring program.

Note: You may choose to focus these steps on a theme in order to keep the process more manageable. The theme might be #1 in Customer Satisfaction and the steps would then focus on that vision for the future. For instance: What is possible, in our billing department, to ensure we are #1 in Customer Satisfaction?

Benefits of Appreciative Inquiry Integrated with a Curriculum

When this type of activity is integrated with a Teaching Thinking curriculum, it exposes those enrolled in the curriculum to new ways of thinking that they simply would not come up with on their own. It also exposes them to real-world experience and capabilities, rather than contrived activities with expected outcomes. Finally, it unites the organization because everyone has a hand in the creation of the future (there are elements of social constructionism in this type of learning activity).Combining vision and experience enables an organization to reach new heights.

Why Knowledge Management is NOT the Answer

4 Levels of Learning Outcomes

According to Wikipedia, Knowledge Management (KM) is the process of creating, sharing, using and managing the knowledge and information of an organization.

At first-read this sounds like a great idea, and many organizations have spent many millions of dollars in the last 20 years to collect and catalog the knowledge their employees possess, in order to "preserve" it and share it.

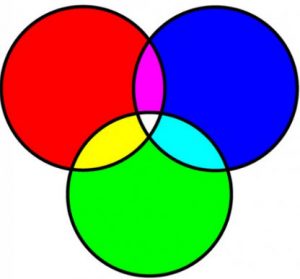

There is one glaring problem with this approach - knowing what you know and knowing how you arrived at the answer are worlds apart. As the illustration shows us, knowledge is at the lowest level of learning. Indeed it is the foundation upon which all learning, skill and ability is built, but having knowledge alone is not enough.

For individuals and organizations to have success, there needs to be a transfer of thinking skills- not just information. For example, in one organization we've worked with, the transfer of thinking skills started with asking senior associates to write a short synopsis of the six "defining moments" of their career - when did they have an “ah-ha” moment and how did it change how they worked? These were then categorized in to themes such as loss, growth, conflict, strategy, competitive advantage, etc.

The same senior associates were then interviewed to get more detail about their "stories" - what they had learned and how. Questions such as, "Was there a single factor that influenced your _____," or "If you had the opportunity to give advice to your younger self, what would you advise?"

Finally, the "best" stories in each category (loss, growth, etc.) were chosen and those same senior associates were interviewed, on camera, a'la 60 Minutes, to tell their story in five minutes or less. The previous steps of writing the story out and thinking aloud through interviews helped the associates to succinctly transmit the situation, the outcome and the lessons learned.

In just under two months the organization captured the best thinking from the most experienced people in the organization. The videos were used as "teasers" to get learners interested in the topic (theme) and the other stories were made available in a case study format for learner's reference.

The collection of thinking is available to be disseminated via multiple modalities - on the company's intranet, via a monthly internal newsletter, on-demand from the learning portal, and in leadership training offerings.

An interesting outcome of the project is that other associates have come forward to voluntarily share their thinking as well. They want to share their career defining moments and learnings with the organization and other associates. The organization now has an archive of what, why, and how, rather than a collection of simply what.

Invest in Critical Thinking = HUGE ROI

Some organizations still believe training is a cost-center rather than a money maker.

But the right training, applied at the right time, can have exponential returns! According to this short report on Critical Thinking, published by Pearson in 2013, the return on investment for critical thinking tends to be extremely high. Research has shown that when training moves a $60,000 a year manager or professional from “average" to "superior," the ROI is $28,000 annually. (emphasis, ours) 4

How would your organization like to make $28,000 per year, on each of its managers? We can help. It's what we do.

Smart Pills - Is it Possible to Enhance Your Thinking?

are smart pills real?

Thinking - like any skill - requires practice to improve... right? What if there was a way to make yourself smarter with no effort? What if you could just pop a pill to increase cognition?

The smart pill idea was introduced to the mainstream by the movie Limitless in 2011 (and subsequently a TV show by the same name in 2015).In the movie the main character, Edward Morra, is able to become hyper-focused, productive and perceptive through the use of a nootropic drug called NZT-48. He is able to write a book in four days, make rationale and spot-on stock picks and more.

Believe it or not, there is some truth to this. Many ADD / ADHD medications are considered smart pills - not because they make people smart(er) but because they can help people to focus and concentrate - thereby being better able to take-in and process information. Just as a computer enhances efficiency by helping you to create and store information, a smart pill can increase mental efficiency and abilities.

The most commonly used smart pill in the US is Modafinil - which is used off-label for increased wakefulness and focus. The original purpose of the drug is to solve narcolepsy and certain types of sleep apnea. A 2008 article by TechCrunch founder Michael Arrington dubbed it an entrepreneur's "drug of choice" as opposed to illicit drugs which might cause addiction (Modafinil has no side effects and is not habit forming), although he does question the wisdom of staying up 20 hours straight.

It Works

In addition to anecdotal evidence that nootropics work, a meta-analysis of 24 studies was conducted jointly by researchers at Harvard Medical School and Oxford, which showed that Modafinil does indeed increase cognition. What's interesting is that the most benefits are derived in relation to complex tasks such as planning and decision making - as opposed to simpler tasks such as pressing the right button at the right time. Given today's business environment, which requires quick and complex thinking tasks - Modifinil might be the next required "tool" in a company's toolbox.

Increased Focus Isn't Always the Best Outcome

The Harvard / Oxford study also cautioned that focused thinking is not always the desired outcome. There is evidence that divergent thinking is inhibited by the drug, so jobs and tasks that demand creativity and innovation may suffer.

Do Smart Pills Create an Ethical Dilemma?

The use of smart pills poses some questions for the workplace, such as: should stimulant use be banned or approved? We do allow caffeine and nicotine which have similar effects. How do we differentiate or draw the line for a drug such as Modafinil?

The TechCrunch article joked that venture capitalists might require business owners to take the drug, to ensure their investment / company success. Some colleges are already banning the use of these drugs (Duke University has revised its policy on drug-use to include banning "unauthorized use of prescription medicine to enhance academic performance"); but other "smart drugs" include Ritalin (which increases memory and retention) and Adderall, so aren't schools then penalizing young people who need these medications? (Note: The percentage of young adults prescribed ADD / ADHD medication nearly doubled between 2008 and 2013.)

Research suggests that cognition-enhancing drugs offer the greatest performance boost among individuals with low-to-average intelligence (Scientific American March 1, 2016). So banning the drugs could harm both those who need it and those who could most benefit from it.

We ask these questions because this is where the discussion is happening right now, but give it a few years and we'll be having these same discussions in the workplace - either because everyone will be looking for an advantage in order to get ahead, or because the youth who have relied on these medications for success in childhood will graduate to working in business and may still be taking these cognitive enhancers.

Bottom Line

The bottom line is - smart pills don't increase the size of your brain or the number of neurotransmitters, or make you able to learn something you aren't inherently able to learn in the first place. They simply help you to focus for longer periods of time, thereby increasing your abilities related to complex cognitive tasks.

When it comes to learning, one millennial cautions: While smart drugs allow for instant improvement, they overlook what can be learned from the process of improving. Here here!

Would Your Employees Train on Their Own Time?

"The company has to look forward and transform. If it doesn’t, mark my words, in 3 years we'll be managing decline." [2016] Randall Stevenson, CEO of AT+T

AT+T has been swimming upstream for 20+ years now.

Long gone are the times of one landline in everyone's home. In order to survive, the company has adapted to, embraced, and conquered cellular networks, cable television, fiber optic networks, satellite networks and streaming networks - all on a national scale.

In order to keep up with the rapid changes in technology and infrastructure, their employees have had to constantly change, adapt and grow as well.

Is your company forward-thinking enough to do what AT+T has done?

Between 2013 and 2016 AT+T spent $250 million on employee education and professional development programs. According to Stevenson, the CEO, employees are expected to put in 5 - 10 hours a week in professional development - on their own time. The company pays for or supports their educational efforts but does not directly supply all the training that is needed.

Additionally, the company created their own masters program in conjunction with GA Tech; and then opened it up to the public via Udacity. There were two reasons for this . 1) they couldn't find enough people graduating with the skills that they needed to fill the positions they had open - so they had to create a bigger supply somehow, and 2) Any member of the "public" who enrolls is a potential (well educated) future employee - so they are building a pipeline of skilled employees.

Now THAT's a future-thinking organization.

How Apprenticeships and Teaching Thinking go Hand-in-Hand

If I were to ask you to picture a cell phone - would you picture a baseball sized item, battleship grey, with a silver antenna you had to pull out of the top? Of course not. That is a cell phone of yesteryear.

Yet, when we mention the word "apprenticeship" to organizations or individuals, the most frequent reaction is, "Oh, that's not for us/me; apprenticeships are for manufacturing, hands-on labor, blue-collar jobs."

Not so! Those are apprenticeships of yesteryear.

Welcome to the new era of apprenticeships - they just might save your organization.

On June 29th President Trump signed an Executive Order - Apprenticeship and Workforce of Tomorrow - to expand apprenticeships in the US. The goal is 5 million apprenticeships in the next 5 years (currently there are 450,000 registered apprenticeships in America).

It shall be the policy of the Federal Government to provide more affordable pathways to secure, high paying jobs by promoting apprenticeships and effective workforce development programs.

According to the Department of Labor, companies in all sectors of the American economy are facing complex workforce challenges and increasingly competitive domestic and global markets. Apprenticeships are one key to helping people who have been left behind by shifts in the economy and how work is done.

The Success of Apprenticeships

Apprenticeships are a standard route to a career in much of Europe. Germany, especially, is known for its exceptional apprenticeship model. In Germany, half of high school graduates choose a track that combines training on-the-job with further education at a vocational institution (as opposed to the US, in which less than 5% of young people participate in apprenticeship programs). The mainstream nature of apprenticeships in Germany contributes to the country having the lowest youth unemployment rate in Europe.

Apprenticeships are an acceptable and highly respected alternative to college. At the John Deere plant in Mannheim, over 3,000 young people a year vie for 60 apprentice spots; likewise, at Deutsche Bank in Frankfurt, over 22,000 applicants vie for just 425 places.

Another benefit that Germany reaps from its well-seasoned apprenticeship program is keeping manufacturing jobs in the country. However, apprenticeships are no longer focused solely on manufacturing or "trades." Apprenticeships are now common in IT, banking, hospitality, and healthcare.

In the future, there will be robots to turn the screws. We don't need workers for that. What we need are people who can solve problems - skilled, thoughtful, self-reliant employees who understand company goals and methods. (German educator)

Perhaps it won't work in America

There are a number of reasons why apprentice programs may not work in America, unfortunately. Naysayers cite costs, stigma, cooperation, changing belief systems, and turning a big ship around. In short, it's not going to be quick, and it's not going to be easy.

In the United States there is a tendency toward higher education as the path to career options, although a recent article in the Chronicle of Higher Education admits "something about the path from college to career is not working for many people. “In recent decades we've seen corporate America severely reduce the budgets of training departments and cut back the hours allotted for training, per individual. The cost of apprenticeship programs is largely borne by the employer (German companies say their costs range from $25,000 to $80,000 per apprentice) and take two to six years to complete.

One program, at a Siemens plant here in the US (Charlotte NC), reportedly spends $170,000 per apprentice. Cost should be seen as an investment, say German proponents. Rather than looking for immediate ROI, companies need to look to longer-term benefits such as a ready and able talent pool, long-term employees (studies have shown that apprentices stay with the company that trained them - a loyalty is established), and workers who understand their organization's culture and goals. Additionally, there is a social component - skilling individuals for blue-collar, white-collar, and jobs of-the-future is one of the best ways to cure income inequality.

Americans aren't simply going to jettison old attitudes and decide, for example, that long-term gains, however broad, should trump short-term ROI.

Unlike in Europe, where apprenticeships are integrated into the educational system (in Switzerland students are introduced to apprenticeships as early as fourth grade and Swiss high schoolers are ready to work upon graduation, having started their apprenticeships around age 15).

The minimal apprenticeship programs currently available in the US are "marginalized and have almost no connection, or very limited or tenuous connections, to either our secondary-education or our higher-education systems," says Mary Alice McCarthy, who directs the Center on Education and Skills at the think tank New America.

Despite these perceived drawbacks and challenges, the Department of Labor is ready to help those organizations that do want to begin apprenticeship programs.

The Benefits of Apprenticeship Programs

First, the benefits to individuals: The benefit most widely touted is "college without debt." Apprenticeships always include some form of higher education; sometimes the ratio is 1:1 (equal amounts of time in the classroom and on the job) and sometimes the proportion varies one way or the other. Many apprenticeships culminate in a two-year degree, but the length of time to achieve it may not be exactly two years. If one is enrolled in an apprenticeship, the employer pays for most, if not all, of the tuition with the associated college. Generally employers partner with local colleges (such as community or technical colleges).

Another individual benefit is "earn while you learn." All internships are paid positions. The apprentice does not make the same wages as a fully qualified individual in the role, but that is offset by the amount of tuition they are the beneficiary of. Also, once the apprenticeship is completed, the individual's compensation usually rises substantially.

Other advantages include having a "foot in the door," having re-marketable skills (although, as cited earlier, most apprentices stay with the employer that trained them), and a work-record that aligns with their degree (as opposed to most college graduates who have a degree but no real-world work experience).

Likewise, there are substantial benefits to the employer: One of the most attractive benefits of instituting an apprenticeship program is the ability to "grow your own." Even if companies can find qualified individuals in the general population, oftentimes they come with abilities that don't mesh with the new employer.

For example, the Dartmouth-Hitchcock health system in Lebanon NH runs a 15-month long apprenticeship program to train medical coders, pharmacy techs, and medical assistants. The program was instituted to fight the constant battle of trying to find appropriately skilled individuals in the local area, but the health system's director of workforce development also cited the challenge of hiring workers from other hospitals in the area who "often don't have the same level of competence."

An apprenticeship program also ensures a steady-stream of skilled individuals for the key roles an organization has identified. Rather than trying to beg, borrow or steal already trained employees from other organizations (which doesn't ensure the "ideal" candidate and can cost tens-of-thousands of dollars in recruiting, interviewing and onboarding costs) an employer knows the quality and capability of the apprentices in their pipeline. Apprentice programs quell the panic of "where will we find xxx?"

Apprentices have also been "schooled" in the company culture, work-ethic, values, processes, etc. Many employers cite these intangibles as "invaluable." For instance, at Bosch, a manufacturing organization with facilities in Germany, as well as South Carolina, US, a mistake on the factory floor can potentially cost a million dollars; the director of the apprenticeship program says that the company is confident in the skills as well as the level of responsibility their apprentices have when on the job. In many ways apprenticeships offer a substantial return on investment.

Apprenticeships are no longer limited to manufacturing or construction, as in the past. Today's apprenticeships prepare individuals for careers in healthcare, IT, financial services, insurance and more. In fact, instructional design would make an ideal apprenticeship topic because it is a nuanced skill with much theory to know and practice required to master.

Finally, the Department of Labor is ready with grants and support to help organizations begin apprenticeship programs. The DOL cites benefits such as attracting a new and more diverse talent pool, investing in talent that keeps pace with industry advances, and closing gaps in workers' skills and credentials which undermine productivity and profitability.

Apprenticeship Programs Align with Teaching Thinking Skills

Many of the approaches and benefits of apprenticeships are also built in to a teaching thinking curriculum.

The extended timeline for learning (years, not days or hours), the on-the-job experience and practicality, the incorporation of coaches or mentors, teaching soft-skills such as teamwork and self-management, the structured nature of the learning process which ensures that all participants are learning the same skills in the same order and on the same timetable, the focus on white-collar jobs, and more.

Soft skills are actually better taught in a business environment than they are in a classroom. In a classroom the consequences are very different.

How to Get Started

If your organization would like to explore the possibilities of an apprenticeship program, call us, or go to the Department of Labor web page for resources such as a Quick-Start Toolkit, a list of tax incentives and credits, and information on how to access federal funding to build your program and / or pay stipends to your learners.

Where do Attorneys Come From?

If you work for a large enough organization, you undoubtedly have a law department.

Have you ever wondered where the attorneys come from? Not straight from law school, that's for sure. Your organization acquired them from somewhere else - usually from a law firm.

Law firms are in an unenviable situation. First, they must deploy employee training from day one - law school does not make one an attorney, it simply teaches one about the law. Second, the average tenure at a law firm is 5.4 years. And, most lawyers who leave their firms do not go to another firm - they usually go to corporate America.

So, you're welcome. Law firms are footing the bill for you to the tune of $200,000 per attorney according to our source.

What roles would you train for - from scratch - in your organization? What jobs does the organization prioritize? How does your company stay in business - who are you dependent on? How much is your company willing to invest to "grow" a stellar employee? See this related article for some ideas on how to training employees from the ground up.

Do YOU Have 30 Years to Wait to Develop Leaders at Your Company?

Organizational Development research tells us that it takes 30 years of on-the-job experience for someone to acquire enough well-rounded skills to be a successful leader. In addition to on-the-job experience, it is important to have experience in numerous areas of business. Hence time on-the-job + exposure to many areas of business = a C-level individual with the perspective needed to run an organization. But thirty years? Who has that kind of time?

Here are a few profiles of organizational leaders who have been on that 30 year journey:

Mary Barra, Chairman and CEO of General Motors

Prior to becoming the CEO, Barra worked in product development, purchasing and supply chain, human resources, global manufacturing engineering, as a plant manager, and in several engineering and staff positions. She joined GM in 1980 and spent her entire career (30+ years) at the company.

Doug McMillon, CEO of Walmart

McMillan joined Walmart as a teenage warehouse worker (in 1984) at a local store. He rose through the ranks, working as a buyer, in various levels of store management, and eventually headed up Sam's Club and Walmart's international operations (operating in 26 countries outside of the US).

Ginni Rometty, Chairman, President and CEO, IBM

Prior to being promoted to CEO, Rometty held senior-level positions in sales, marketing and strategy. She began her career at IBM in 1981 as a systems engineer and worked in IBM Consulting as well.

Not everyone has to be a "lifer" within an organization, however. Generalized business experience is helpful as well.

Kenneth Frazier, CEO of Merck & Co.

Frazier spent 20 years as a trial attorney - spending numerous summers teaching trail advocacy in South Africa - before joining Merck as counsel in the public affairs division in 1992. From 2007 to 2011 he led the Human Health division of Merck, before being named President in 2011 and then CEO in 2014.

The most prominent trait of these CEOs (and undoubtedly thousands of others) is the variety of roles and functions within which they worked (and learned). In fact, two separate articles by Forbes in 2015 and the NY Times in 2016, point out the "path to CEO" is dependent on well-rounded experience and experience in many functional areas.

This is an approach that corporate education could support, but rarely does. We tend to "silo" people in to a role or function and encourage them to become a specialist; concentrating all of their experience in that specialist area.

From the NY Times article:

Marc Andreessen, the prominent venture capitalist, has gone so far as to call [well-rounded experience] the "secret formula to becoming a C.E.O." The most successful corporate leaders, he wrote, "are almost never the best product visionaries, or the best salespeople, or the best marketing people, or the best finance people, or even the best managers, but they are top 25 percent in some set of those skills, and then all of a sudden they're qualified to actually run something important."

We Don't Have That Kind of Time

Unfortunately, we don't have 30 years to get our next generation of leaders ready. In order for our companies to remain vital 15 to 20 years from now (when the Boomers, with the most work-experience are all gone) we need a way to accelerate that well-rounded learning. T

he Training Doctor's Thinking Curriculum has one such answer. The customized curriculum is designed to facilitate the very things that make a C-suite leader: a variety of functional experiences, an understanding of finance and strategy, being able to synthesis information about unfamiliar situations, networking and making connections, and more (these attributes were identified in a 2016 study of 459,000 executive profiles via LinkedIn). The best part of The Training Doctor's Thinking Curriculum is that it allows an organization to "bring up" leaders from within the organization which is often critical in terms of historical knowledge and cultural fit.

A recent publication from DDI, titled High-Resolution Leadership, highlights both the length of time it takes to develop leadership skills, as well as the need to accelerate the process:

"Business has hastened the pace of leaders being thrust into roles of increasing scope and responsibility, ready or not. Too often this leads to a mass "arrival of the unprepared" into more complex and perilous higher-level roles where stakeholder scrutiny and the cost of failure are exponentially higher. Leadership is a discipline. Improvement requires learning, practice and feedback - lots of each. But generic skill development won't provide the capability you need for your business. Any efforts you make to accelerate the growth of leaders should train them to apply newly learned skills to the specific challenges and needs that your organization faces now and will face in the near future."

It's folly to focus solely on leadership development, however. It's in every organization's best interest to build the skills of everyone in the organization. What organization can say they don't need people who understand strategy, problem solving, risk management, or decision making? What organizations would rather get-by with employees who don't have self- management skills (as Uber's CEO Travis Kalanik recently demonstrated) or who don't embrace ethics, teaming, or continuous improvement?

Every organization and every individual can benefit when everyone's business-acumen is enhanced. Learn more here or give us a call to see what your customized curriculum might look like.

Why the Ice Bucket Challenge is a Great Example of a Lack of Thinking Skills - but an awesome fundraiser!

Do you remember the "ice bucket challenge" of a few years ago? It was a fundraiser of the ALS Association. ALS is also referred to as Lou Gehrig's disease.

In case you are not familiar - the challenge was to dump a bucket of ice water over your head (or have someone do it for you) OR make a donation to the ALS Association.

One of our colleagues uses his Ice Bucket Challenge experience to illustrate the lack of thinking skills prevalent in society: His children challenged him, via social media, to take the challenge. Seeing the bigger picture, and not really wishing to be drenched in ice cold water, AND due to the fact that he had had a family member die of ALS, he chose option B - making a donation to the ALS Association. His children (who were adults, by the way) were FURIOUS that he didn't "do it." He explained to each of them that the challenge offered two options and that he actually made a bigger impact by making a donation to the cause rather than just a silly video. No matter. To this day they rib him about not being brave enough to take the ice bucket challenge.

What thinking skills do you see as lacking in this scenario? Here's what we see:

Inability to see the "big picture"

Not understanding the purpose of a request - but going along with it anyway

Group think

Choosing to ignore facts that don't "suit" you

Not asking about or looking for alternate "solutions"

Not looking for (or understanding) long-term ramifications

When working with your learners - the above bullets can be used as great discussion starters for any topic. Just pause. Look at the big picture. Seek alternatives. Think individually. Is this a solution for "right now" or more long term? What are the options? What is the best option?

= = = = = = =

Facts about the Ice Bucket Challenge

17 million people doused themselves with cold water; 2.4 million people posted videos of themselves on Facebook

2.5 million people donated money to the cause during the challenge; close to 1 million made no subsequent donations

$115 million dollars was donated to the ALS Association in 8 weeks!

The year prior to the ice bucket challenge the ALS Association received $19.4 million in donations

People who chose the ice water over a donation were referred to as "slacktivists" or arm-chair activists

The success of the ice bucket challenge caused the Muscular Dystrophy Association to end its annual telethon fundraiser citing its need to "rethink how it connects with the public"

One death was attributed to the challenge

The Ice Bucket Challenge has become an annual "event" held in Aug - so get your video camera's ready (or, preferably, your checkbooks)

How to Build a Better Leader

While we often repeat Malcolm Gladwell's premise, in Outliers, that it takes 10,000 hours to be an expert at something, we rarely apply that idea to soft skills - like leadership. And that is quite possibly why we have such a tough time cultivating leaders in our organizations.

Joshua Spodek, author of the bestselling Leadership Step by Step: Become the Person Others Follow likens leadership skills to athletic or acting skills. You must participate, you must start small and perfect different aspects of the craft, you must put yourself in situations beyond your comfort zone to really explore and understand your capabilities. You aren't simply "gifted" the title (or skill) of leader.

Tom Brady recently led his team to a 5th Super Bowl win. But he didn't join the Patriots as a leader. In fact, he was a sixth-round draft pick (the 199th player to be picked!) and, when he joined the team, he was one of four quarterbacks (that's two too many by most NFL team standards). Luckily, Brady was able to hone his skills (both athletic and leadership) while out of the spotlight - the rest is history.

Jennifer Lawrence is the highest paid female actress. It seems as though she just exploded on the scene but in fact she started her "career" in school musicals and church plays. Her first time onscreen was in a supporting role 10 years ago. She's acted in dramas, comedies and sci-fi movies. She has been the lead...and part of an ensemble. She has honed her craft and is viewed as a bankable star in Hollywood.

How Can We Create Our Own Bankable Stars?

According to Spodek, the first crucial skill to master is self-management. One cannot manage others unless he / she is in command of himself.

Next is communication skills. Spodek rightly points out that people hear what is said - not what is meant. Remember, it's the speaker's responsibility to ensure their message gets across.

The third key development opportunity is our favorite - constantly seek growth. Yes, increasing knowledge and skills in one's industry is a given, but Spodek suggests leaders-in-training should examine and challenge their core beliefs in order to be open to all possibilities.

Finally, Spodek stresses the importance of being comfortable with emotions - both one's own and one's employees. He suggests finding out other's passions in order to lead them in the way they want to be led. Daniel Goleman expresses this same sentiment but refers to it as empathy.

As you can imagine, none of the skills, above, are developed without devoted effort and analysis of what works and what doesn't. A little coaching doesn't hurt either - because it's nearly impossible to say to oneself, "You know what I lack? Self Management." (Thank you, Travis Kalanick, for shining a spotlight on that one.)

Leadership skills should be SOP (standard operating procedure), in terms of training, at all organizations. If your organization doesn't train for these - start today - before you find yourself with no quarterback.

Better Decision Making Through Reducing Bias

Lately we’ve been hearing a lot about the word “bias;” usually in the context of unconscious bias as it relates to talent management decisions in the realm of diversity, inclusion, and recruitment. If you Google the phrase “Unconscious Bias + Talent”, you’ll come up with over 150,000 articles and resources in this vein!

But truly, the word bias has no specific implication. It simply means to be prejudiced for or against something, in comparison with something else (I am biased towards white chocolate, for example). Most of us would declare that we are unbiased, thinking that it is the right, or best, state to be in. But truly, there is no way to be unbiased. A lifetime of experiences, “lessons learned,” and repetitive cause-and-effect relationships have created biases that exist in our unconscious (according to Malcolm Gladwell in Blink: The Power of Thinking Without Thinking). Generally we simply aren't aware of our biases.

The Power of Bias

Bias is almost a safety mechanism – with more than 11 million pieces of information coming at us every day, and the brain’s capacity to process only about 50 pieces of information at a time – if we didn’t have mental shortcuts, like bias, we’d never get through the day. In fact, unconscious processing in the brain governs the majority of important decisions we make. “What this means is that because we have brains, essentially we are all biased” (Andrea Choate, SHRM’s Neuroleadership Lessons: Recognizing and Mitigating Unconscious Bias in the Workplace).

Neither good nor bad, the brain is simply hardwired toward this tendency.

The Bias Impairment

Unfortunately, the brain is unable to make a decision while simultaneously noticing whether it is a biased decision. This can be risky both for individuals and for our organizations. Since we aren’t able to “see” bias – either in ourselves or in others – it’s imperative that we work proactively to raise awareness of bias and take action to mitigate it so that our employees are making the most fully informed and well-reasoned decisions possible.

Typical Bias in Decision Making

There are various forms of bias in the workplace – in relation to decision making. It’s possible you’ll recognize yourself in one or more of these examples (just by writing this article I’ve recognized a sunk cost bias – coupled with groupthink – that has been plaguing a non-profit board on which I sit).

Status Quo – Are you familiar with the Irish proverb: Better the devil you know than the devil you don't? That is the essence of a status quo bias. In other words, you’ll make a decision based on what has worked in the past rather than taking the time to evaluate if “business as usual” is still working.

Sunk Cost – The sunk cost bias causes us to throw more money and more resources at a lost cause because “we’ve put so much in to it so far,” rather than accepting that things are not working. Remember New Coke? Coca-Cola did NOT suffer from sunk cost bias. They did an immediate about-face to recapture customer loyalty and market share.

Confirmation – Confirmation bias causes us to seek out information or evidence that confirms what we already believe (and, conversely, to discount information that is not congruent). This might be demonstrated in performance reviews: Charles stays past closing two or three times a week and often comes in on Saturday – clearly he is a stellar performer. (Or, is it possible, Charles is in over his head and needs the extra time to keep up?) (See cartoon at the end of this post.)

Group Think – The Challenger Disaster has been widely attributed to group think bias – when we try to fit in to a particular group by mimicking their behavior or holding back on sharing thoughts that are counter to what the group is leaning towards.

Anchoring – We have the tendency to rely on the first piece of information available rather than seeking out and fully evaluating multiple sources of information. Many people who are promoted because they were “smart” or “the best” have a hard time delegating for this reason (no one can possibly do this as well as I can). Credit card companies use an anchor by identifying the “minimum payment” clearly rather than the total debt. The minimum payment makes the consumer think, “That’s not so bad.”

Ethics –Everyone thinks they behave ethically. Yale psychologist David Armor calls this “the illusion of objectivity.” Because I have made the decision, of course it is ethical. Think about the recent VW or Wells Fargo scandals. We have to presume the offenders didn’t say “This is a very bad decision, but I’m going to make it anyway.”

So How Do We Overcome Bias?

Like any problem – the first step is admitting that you have a problem. Awareness of bias is key in being able to identify and counter it in our decision making. Although, as stated at the beginning of the article, the ability to make “snap” decisions based on our past experiences and lessons learned is crucial, it’s also wise to pause and assess:

Do I have all the information? Is there better (or different) data I could gather?

What would someone else do in this situation (ask for differing perspectives)?

Is our workplace a safe place to “call out others” on what might be driving their decisions? A phrase as simple as “How did you arrive at that decision?” is often a powerful reminder to evaluate what contributes to one’s decision making.

What would be the “opposite” of what everyone else is doing - and does it have merit?